Explore the Ubi sunt Anglo-Saxon motif

Last week, it became time for my seniors to read and study The Wanderer, the Anglo-Saxon elegiac poem that explores human isolation, loss, and exile. It’s a beautiful poem that connects our contemporary emotions and longings to those of our forebears and shows us, once again, that we can find consolation and instruction in even pre-medieval poetry.

The Wanderer is yet another example of Anglo-Saxon poetry that reveals why we read: to know we’re not alone.

However, while our study of The Wanderer included taking notes, reading the poem aloud, and completing this close-reading scavenger hunt activity, this year I wanted us to go one step further to get more out of this beautiful verse.

So when I read about something called the Ubi sunt motif present in The Wanderer, I took notice… especially when I considered how it might be a way for students to better connect to this poem.

What is the Ubi sunt motif?

I first stumbled upon the Ubi sunt motif as I was reading my trusty Norton Anthology of English Literature (Sixth Edition).

On page 68, in the introduction to The Wanderer, the editors explain that in the poem when the theme “expands from one man to all human beings in a world wasted by war and time,” the speaker waxes philosophically about his past. The text reads, “He derives such cold comfort as he can from asking the old question, Ubi sunt? — where are they who were once so glad to be alive?”

Hmmm, I thought. That’s interesting. I then did some quick online research and located more about Ubi sunt on a literary review blog called Universe in Words. This is how ubi sunt is defined by this blog’s unnamed author:

“The name for this motif comes from the Latin phrase ‘Ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt?‘ which means ‘Where are those who were before us?‘. This is called an erotema, a rhetorical question, and forms the beginning of many Latin poems which ponder upon the concepts of mortality and the transience of life, while also calling strongly upon a sense of nostalgia. Considering the former it should be no surprise many of these poems were Christian, extolling the virtues of living a good life since all perishes and only Heaven is a reward. However, this tradition was also extremely well-represented in English literature as early on as in the Anglo-Saxon period.”

The universe in Words: TOLKIEN, ‘THE WANDERER’ AND THE UBI SUNT-TRADITION

This blogger went on to include a short clip from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers that shows the character Theoden suiting up for the Battle of the Hornburg. In this clip, the screenplay includes lines from J.R.R. Tolkien that draw directly upon the Ubi sunt motif found in The Wanderer. Here’s that video:

In my school’s Prentice-Hall British Literature textbook, the version of The Wanderer is a translation by Burton Raffel. Lines 86-94 feature the poem’s Ubi sunt motif. Here are those lines:

Where is the war-steed? Where is the warrior?

Where is his war-lord?

Where now the feasting-places? Where now the mead-hall

pleasures?

Alas, bright cup! Alas, brave knight!

Alas, you glorious princes! All gone,

Lost in the night, as you never had lived.

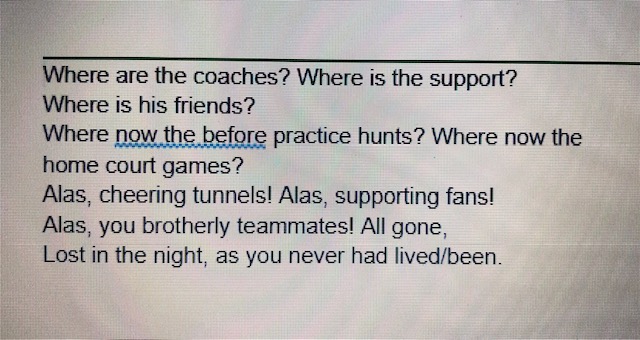

These lines form the basic Ubi sunt within this poem, and I thought they might serve as a template my students could emulate to create their own Ubi sunt poems.

I created an Ubi sunt poem handout for students that includes a little background, some brief instructions, and a mentor poem that I wrote. It’s available on my Teachers Pay Teachers store. Here’s a photo of the handout:

You’ll probably notice that on the handout I included four preceding lines of the poem to introduce the traditional eight-line ubi sunt lines. I thought this would better provide students with more context for the Ubi sunt questions.

In addition, I left it open for students to end their Ubi sunt lines with their choice of “…as you never had been” or “…as you never had lived.” Depending on their approach, I thought either verb would work and still keep the central intention of the Ubi sunt lines: to reflect on their past glories, fond memories, ancestors, etc.

This poetry activity was brief and required only about twenty minutes for students to craft. The next time I try this with my classes, I may see if we can incorporate more peer review. I may also ask students to record themselves reading their Ubi sunt poems to add more personalization to the assignment and to add a “speaking and listening” standard.

My students’ Ubi sunt poems

More Ubi sunt encounters

Once you know a little about the Ubi sunt motif, you may start to see it elsewhere. In fact, my British literature class will no doubt encounter it later this year when we read Sir Philip Sidney’s “Astrophel and Stella” sonnet 102, which asks:

Where be the roses gone, which sweetened so our eyes?

Where those red cheeks, which oft with fair increase did frame

The height of honor in the kindly badge of shame?

Who hath the crimson weeds stolen from my morning skies?

My students and I may also notice the Ubi sunt motif in a broader context as well. Even if a poem doesn’t possess the identifiable “Where is…” questions, it can be said to exhibit the Ubi sunt motif.

According to the Poetry Foundation, “A number of medieval European poems begin with this Latin phrase meaning ‘Where are they?’ By posing a series of questions about the fate of the strong, beautiful, or virtuous, these poems meditate on the transitory nature of life and the inevitability of death. The phrase can now refer to any poetry that treats these themes.” Knowing this, I’ll be keeping my eyes peeled for these ideas.

Poetry Foundation Glossary

Yes, I’ll be sure to try this Ubi sunt mini-poem lesson when I teach The Wanderer next year in my British literature class. It was just the kind of short-and-sweet assignment I needed to round out our study of this classic Anglo-Saxon masterpiece.

Questions? Comments? Feel free to shoot me a message on my Contact page and I’ll be glad to help.

Need a new poetry lesson?

Enter your email below and I’ll send you this PDF file that will teach your students to write Treasured Object Poems, one of my favorite poem activities. I know your students will enjoy it!

More Anglo-Saxon resources:

Need something else?

ELA Brave and True | Love teaching. Make it memorable.

One thought on “A New Poem Activity for The Wanderer”